01.09.11

Posted in Weather Education at 8:01 am by Rebekah

Have you ever stopped to think what meteorologists and climatologists mean by the words “average” and “normal“?

When your local TV weathercaster tells you that today’s temperature is 10 degrees below normal, do you just assume that average/normal means the average quantity (e.g., temperature) for that time period (e.g., January 9th) over all years in recorded history?

If so, you might be surprised to find that average/normal typically means something else in meteorology and climatology.

The climate of any given place changes over time; the earth as a whole naturally goes through cold, warm, wet, and dry cycles (this is true regardless of man’s impact on the atmosphere). This being the case, taking the average temperature, for example, of New York from the 1800s to 2010 may not give a very good picture of the typical temperature you might expect to find in New York.

In meteorology and climatology, we take the average value of a quantity over a 30-year period ending with the end of the last decade, and call that value the average, or the normal.

This means that from 2001 through 2010, the average annual rainfall for Seattle is defined as the annual rainfall averaged from 1971 through 2000.

Now that we’ve moved on to a new decade, we’ll be moving on to a new set of averages: those from 1981 through 2010.

Will this affect how we define our “normal” weather? Yes. In many cases there will not be much of a difference, but take temperature, for example. The 1970s were cooler than the 2000s, thus the new average temperatures for many places will be warmer.

Permalink

01.03.11

Posted in Weather Education at 8:00 am by Rebekah

Today I’d like to start a weather education series. While some of you may have a background in meteorology, others may be confused at times when I speak of instability and wind shear.

So, beginning with the basics and covering topics such as weather maps and severe weather forecasting, every Monday I will give a short lesson on meteorology. The blog posts will build upon each other, and eventually I will make a list of links to the posts and put it on my website.

————————————————–

What is meteorology?

Meteorology (also known as atmospheric science) is the study of the atmosphere and weather. Climatology is the study of climate.

What is the atmosphere?

The earth’s atmosphere is a thin layer of air extending from the earth’s surface to a height of about 12 km (7.5 miles).

Atmospheric composition:

- Nitrogen: ~78%

- Oxygen: ~21%

- Argon: ~0.93%

- Carbon dioxide: ~0.039%

- Water vapor: variable, from 0 to 4%

- Other trace gases, including ozone and methane

What is weather?

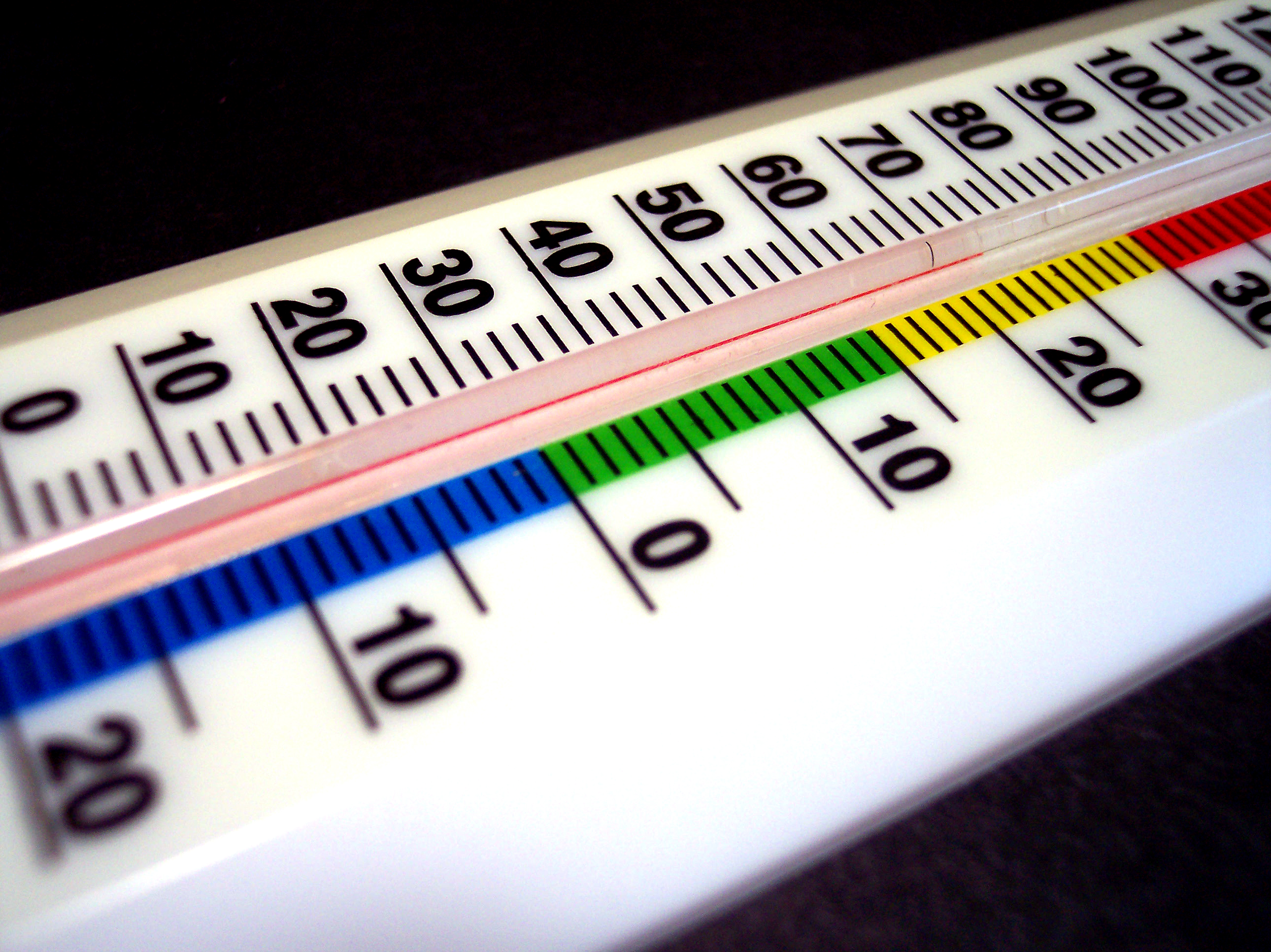

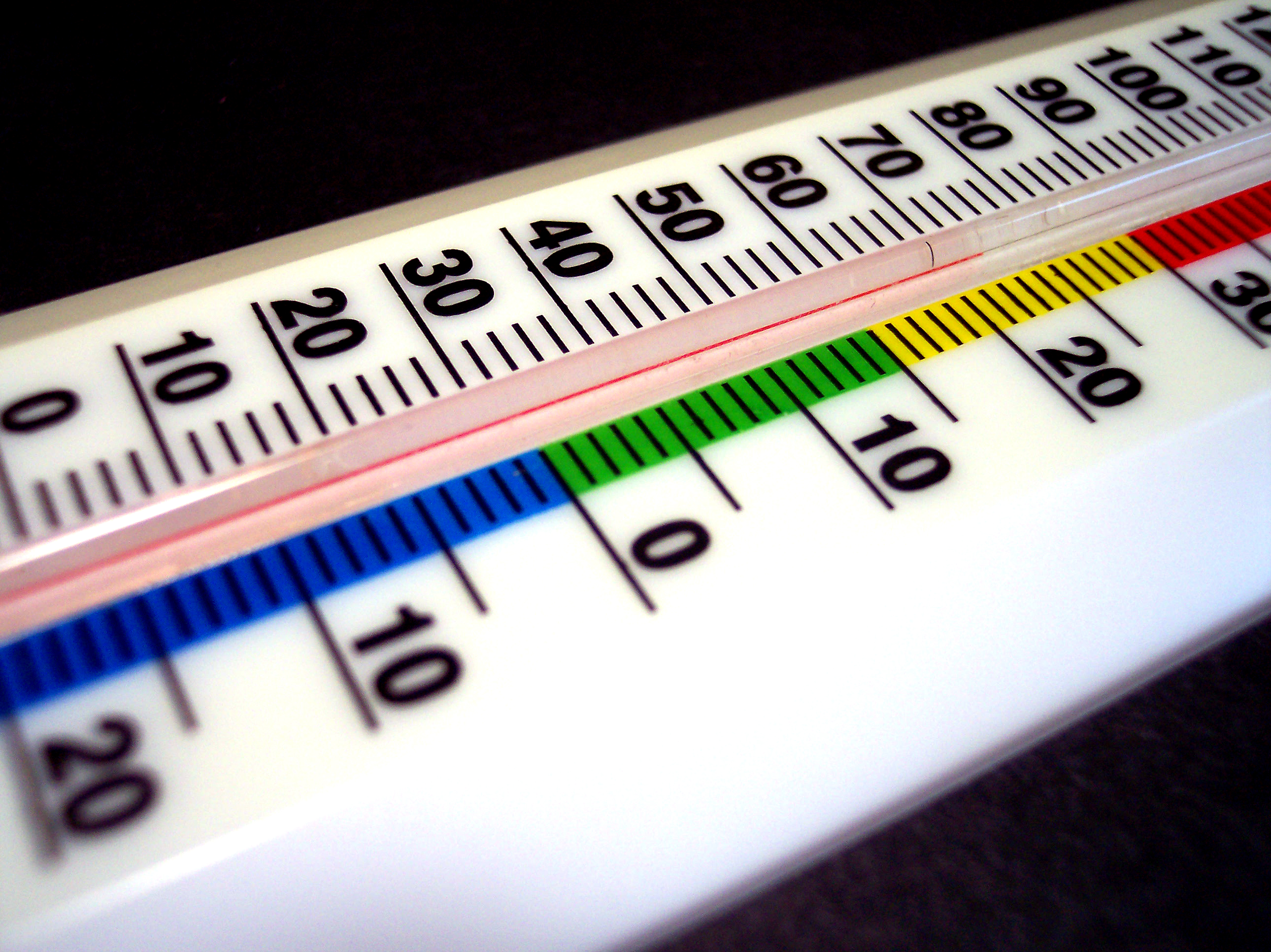

Weather is the state of the atmosphere at any given place and time. For example, the weather conditions at midnight New Year’s Eve 2010 in Seattle, Washington included a temperature of 27 °F, a relative humidity of 66%, calm winds, and clear skies.

Climate, in contrast, is the average weather at any given place over a long period of time. For example, the average high temperature in Seattle for the month of January, a component of the city’s climate, is 46 °F.

Why is there weather?

As described in last week’s post, “What If…We Could Prevent Storms From Occurring?“, the sun heats the earth unevenly (because of earth’s tilt). Some of this radiation is absorbed by the earth, which then emits longwave radiation back to space.

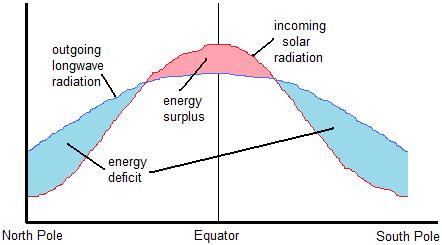

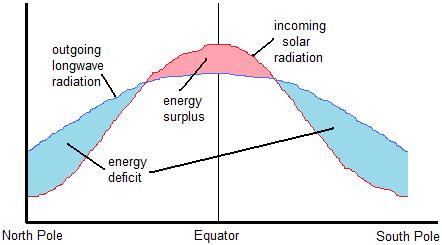

Long story short (check out that blog post for more detail), the tropics receive more radiation than they emit, and the poles emit more radiation than they receive. This means the tropics have a net surplus of radiation and the poles have a net deficit of radiation (see figure, below).

Earth’s Annual Radiation Budget

The earth is always trying to balance out inequalities, though, so warm air must get transported towards the poles, while cold air must get transported towards the tropics! This transfer of air is what drives our weather.

————————————————–

Come back next Monday to learn about the elements of weather, beginning with temperature and the layers of the atmosphere!

Permalink

12.30.10

Posted in Weather Education at 8:01 am by Rebekah

“Everybody talks about the weather but nobody does anything about it.” – Mark Twain

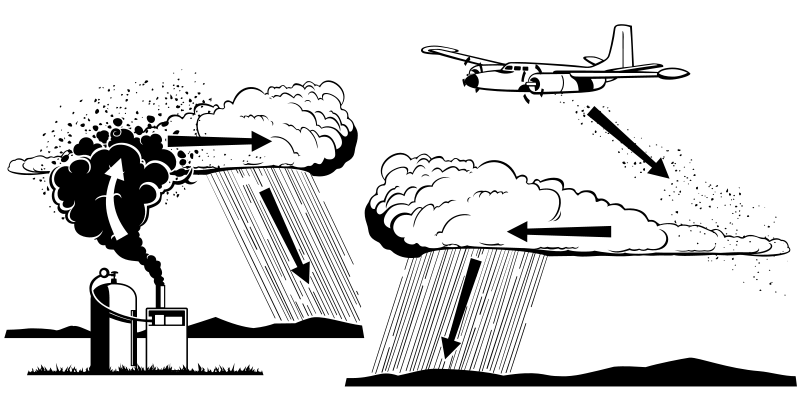

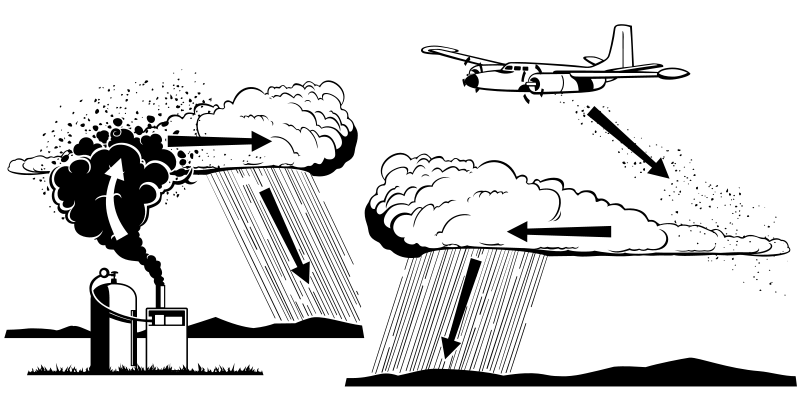

Depiction of cloud seeding. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Monday’s post touched on why weather occurs and why storms are an integral part of earth’s never-ending balancing act. (See What If…We Could Prevent Storms From Occurring?)

The question remains, however, can we change the weather? Maybe we can’t or shouldn’t even try to prevent hurricanes and tornadoes from happening, but can we at least influence their strength and path?

The most common and well-known type of weather modification is cloud seeding. Cloud seeding involves spraying small particles (e.g., silver iodide) into the atmosphere, usually via airplane, in an effort to trigger cloud formation. Water vapor may then condense onto the particles, form clouds, and produce rain.

Cloud seeding has been experimented with in the U.S. (primarily in the Rockies), China, Russia, and a few other countries. Sometimes the goal is to cause rain in drought-prone areas, while at other times the goal is cause rain to fall in one area instead of another. During the Beijing Olympics of 2008, China used a form of cloud seeding to assist in preventing rain from falling (via shrinking rain drops).

While the idea of cloud seeding may seem great, there are a few problems with this method:

- it is impossible to test the effectiveness of cloud seeding (how do we know it wouldn’t have rained there anyway?)

- legal ramifications (what if you make it rain on someone else’s crop when they don’t want it to?)

- it is impossible to generate water through cloud seeding (it only works to the extent that there is already water vapor in the air)

Nevertheless, I find cloud seeding to be an intriguing, if not controversial, form of weather modification.

Another type of weather modification involves the weakening of tropical cyclones by seeding the eyewall with silver iodide. This method was experimented with in the 60s and 70s, with little success.

Hurricane Isabel from the ISS. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Other proposed ways to modify hurricanes include the use of barges with upward-pointing jet engines to trigger smaller storms to disrupt the progress of a hurricane (though this was never tested, as many believed the jets would not be strong enough to make any difference) and the pouring of environmentally-friendly oils on the ocean surface to prevent evaporation and cloud formation (this, too, was later discounted as ineffective).

Some scientists believe there may be a possibility of controlling weather in the future from space. One idea is the heating of large hurricanes at certain critical points, in an effort to steer the cyclones a bit.

Finally, as with cloud seeding, weather modification in general could have the following problems:

- Effectiveness (most proposed methods have been shown to have little to no effect on the weather)

- Legal issues

- Unintended side effects (weather is chaotic and may not always respond the way you think)

- Damage to existing ecosystems (see Monday’s post…we may need storms and certain weather to maintain good living conditions for people, animals, and plants)

- Health risks

- Use as a weapon

In the meantime, the best we can probably hope for is to warn people of certain weather events ahead of time and to educate people on what they should do to protect life and property when dangerous storms do occur.

So what are your thoughts on weather modification? Should we attempt it? Why or why not?

Permalink

12.27.10

Posted in Weather Education, Weather Myths, What If at 10:01 am by Rebekah

Have you ever heard of weather modification?

Has anyone told you (or have you thought) that we would be doing society a favor if we could figure out how to prevent destructive storms such as hurricanes and blizzards from happening?

What do you think the earth would be like if we didn’t have these storms?

Here’s my take on this question.

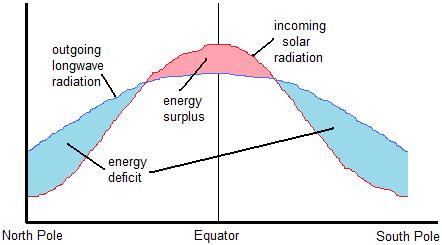

Due to the earth’s tilt, the sun heats the earth unevenly. The tropics receive more direct solar radiation than the poles.

Some of this radiation is absorbed by the earth, which subsequently emits longwave radiation back to space. The tropics, as you might guess, emit more radiation than the poles.

Now, the tropics receive more solar radiation than is emitted by the earth at the tropics…but the poles emit more radiation than they receive. This means the tropics have a net surplus of radiation and the poles have a net deficit of radiation (see figure, below).

Earth's Annual Radiation Budget

Left unchecked, this radiation imbalance would result in the tropics growing increasing hotter, and the poles growing increasing colder!

Now enter fronts, winds, high and low pressure systems, and smaller-scale thunderstorms.

Whenever something is out of balance, the earth (or atmosphere) tries to balance it out somehow. Thus, warm air must be transported towards the poles and cold air must be transported towards the tropics. An extratropical cyclone (a low-pressure system in the mid-latitudes) and its associated cold and warm fronts forms to restore equilibrium to the earth’s temperature differential.

See yesterday’s surface analysis from the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center for an example of this balancing act (click to enlarge):

- Take a look at the red “L” off the coast of North Carolina. This indicates the center of the low pressure system responsible for the ongoing blizzard in the Northeast.

- Lows spin counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere (opposite in the southern hemisphere), thus there are north and west winds that are coming around and pushing a cold front (blue line with triangles) southeastward.

- Note many temperatures (indicated by red numbers) are in the 30s behind the front.

- South-southeast winds are wrapping around the eastern side of the low, behind a warm front (red line with semi-circles) lifting northwestward.

- Note the temperatures behind the warm front are in the mid-60s.

Note also that these large extratropical cyclones usually have smaller storms that form along the fronts and/or around the low (e.g., snowstorms and/or thunderstorms). These smaller-scale storms are also attempting to balance an aspect of the environment that is out of balance. Hurricanes are another animal, but are similarly large low-pressure systems (minus the fronts) that help to balance things out.

All that to say that if we did not have weather, including occasionally severe weather, we might be in even more trouble. There is no way to stop the earth from trying to continually balance itself, but if somehow we could, the earth might soon be unlivable.

What do you think about weather modification or what the earth would be like without severe weather?

Permalink

« Previous Page « Previous Page Next entries »